Thanks go to regular reader and contributor 'Getafix for spotting this article on the LSE website:-

The American physicist Richard Feynman once said that, ‘if you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics…’. He could just as easily have been talking about British penal policy. In the space of just 24 days during the summer of 2019, the government’s approach to crime and criminal justice has been turned on its head.

On 16 July 2019, David Gauke delivered what would prove to be his final speech as Justice Secretary. Returning to the themes that defined his tenure at the Ministry of Justice, Gauke set out his vision for a “smarter” justice system:

I believe the public therefore expect the justice system to focus on rehabilitation to reduce the risk of subsequent offending – and the likelihood of them becoming a victim of crime…. We need to punish for a purpose.Gauke cast doubt on the effectiveness of short-prison sentences and drew attention to recent analysis by the Ministry of Justice which demonstrated that individuals serving custodial sentences of under 12 months demonstrate considerably higher levels of reoffending than those serving community sentences. With reoffending estimated to cost the taxpayer £18bn per year, Gauke expressed his hope that a future Conservative government would follow the Scottish example and introduce a statutory presumption against immediate custodial sentences of six months or less. These choices were outlined more in hope than expectation. Boris Johnson was announced as Prime Minister on the 24 July 2019 and Gauke subsequently resigned from the government.

During the Conservative Party leadership campaign Johnson had used his regular column in the Daily Telegraph to advocate for longer sentences for violent and sexual offenders. This overtly populist rhetoric was quickly translated into government policy. Launching what Downing Street would describe internally as ‘crime week’, Johnson set out his law and order credentials in The Mail on Sunday. His government would come down hard on crime and, with an eye to a possible Autumn election, pledged additional funding for crime control:

- The recruitment of 20,000 new police officers.

- The removal of restrictions on the use of stop and search and the launch of a new pilot programmethat will enable 8,000 police officers to authorise enhanced procedures.

- A sentencing review of the most dangerous and prolific offenders.

- A £2.5bn investment in the construction of 10,000 new prison places.

- A £100m investment in prison security; including the installation of ‘airport-style ‘scanners throughout the prison estate.

While it is tempting to view this volte-face through the narrow lens of personality politics, these events are jut as interesting for what they reveal about contemporary conservativism and the fluid balance of power within the Conservative Party. From Leon Brittan’s reforms of the parole system in 1983 to Chris Grayling’s much criticised privatization of the probation service in 2013, the shifting constellations of power between the One-Nation and Thatcherite voices within Cabinet have often gone hand-in-hand with periods of performative penal populism.

Crime may be a quintessentially conservative issue, but it cuts across several major fault lines within conservative thought and new right politics more generally; pragmatism and authoritarian populism; neo-liberalism and neo-conservatism; the local and the global, a fear of moral decline and an embrace of the free-market. These ideological traditions yield very different perspectives on penal policy-making, but it is impossible to understand how and why these ideas come to find expression in official policy without some reference to the competing demands of political statecraft. As the political scientist Jim Bulpitt noted:

What is statecraft? The crude answer is that it is the art of winning elections and achieving some necessary degree of governing competence in office… It is concerned primarily to resolve the electoral and governing problems facing a party at any particular time.Commentators have rightly drawn attention to the highly questionable effectiveness, fairness and penological basis of these measures, but this is somewhat to miss the point.

‘Crime week’ decoded

Viewed through the lens of political statecraft, the current revival of law and order politics has less to do with crime and rather more to do with current parliamentary arithmetic and the Conservative Party’s future electoral prospects:

First, Johnson’s advisors have borrowed from the Thatcher play-book in seeking to position crime as a ‘wedge issue’ that puts clear blue water between the current government, the Labour Party, and Thresa May’s tenure as Prime Minister. This may prove altogether more difficult to pull off in the current climate.

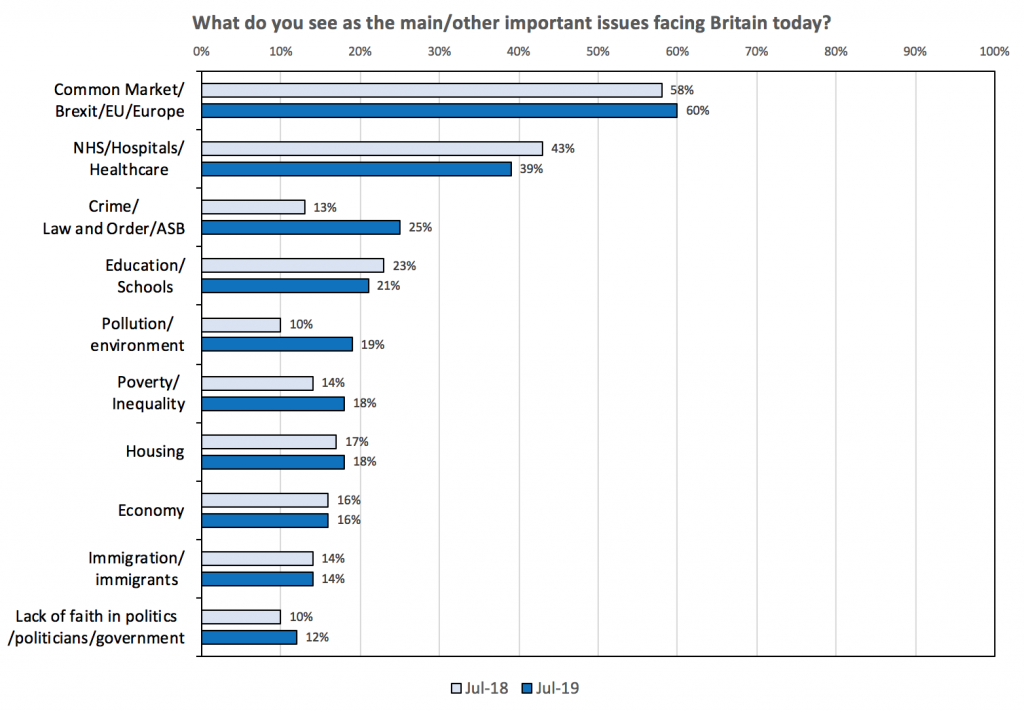

Law and order has barely featured in British general elections since 2001 and it is far from clear that public concern over knife crime and the release of high-profile offenders – such as John Worboys – will break through as a big-ticket electoral issue. As Figure 1 reveals, concern over crime has increased significantly in the past year, but still lags behind Europe and the NHS in the public’s priorities.

Figure 1

Ipsos Mori Issues Index, 2018-2019

Second, in the eyes of many voters Johnson suffers from a credibility gap that was exposed during the leadership contest. His record in government was decidedly mixed and many have questioned whether he possess the temperament to be an effective Prime Minister. In recognition of this, Johnson’s team have repeatedly turned to criminal justice in order to present a counter-narrative based upon his experience as the Mayor of London and the successes (real or perceived) that he had in reducing knife crime across the capital.

Third, Johnson’s government has extremely limited room for policy manoeuvre. The Conservatives have a working majority in Parliament of just one, the civil service is consumed by Brexit planning, and the latitude for additional spending is severely constrained by the current budget settlement. Within such a restrictive operating environment, rhetorical shifts on emotive issues such as crime and immigration can deliver marginal gains despite the fact the underlying legislative or policy framework has remained largely unchanged; a process Steve Farrell et al have characterised as ‘communicative dissonance’.

Fourth, it is increasingly apparent that ten-years of austerity has become an electoral liability for the Conservative Party and a firm point of difference for Labour.

Decoupling the Conservative brand from its cornerstone economic policy, while maintaining a reputation for fiscal prudence, has proved extremely difficult. In this context investment in ‘frontline services’, such as the police, presents an attractive option for policy-makers seeking to square the circle of post-austerity politics.

Brexit: The ‘elephant in the room’….

Ordinarily these measures – in conjunction with recent announcements on public sector pay and the NHS – might be expected to appeal to the Conservative base and some swing voters. But these are very far from ordinary times. The fate of the current government is inexorably linked to Brexit and this single issue will continue to dominate the political agenda to the exclusion of all else. Europe has accentuated longstanding ideological differences within the Conservative Party (as it has within the Labour movement) and this promoted diametrically opposed positions on how best to respond to the challenges of contemporary statecraft.

The sudden change of direction on penal policy this summer may be the latest manifestation of this conflict, but it is unlikely to be the last.

Thomas Guiney

Second, in the eyes of many voters Johnson suffers from a credibility gap that was exposed during the leadership contest. His record in government was decidedly mixed and many have questioned whether he possess the temperament to be an effective Prime Minister. In recognition of this, Johnson’s team have repeatedly turned to criminal justice in order to present a counter-narrative based upon his experience as the Mayor of London and the successes (real or perceived) that he had in reducing knife crime across the capital.

Third, Johnson’s government has extremely limited room for policy manoeuvre. The Conservatives have a working majority in Parliament of just one, the civil service is consumed by Brexit planning, and the latitude for additional spending is severely constrained by the current budget settlement. Within such a restrictive operating environment, rhetorical shifts on emotive issues such as crime and immigration can deliver marginal gains despite the fact the underlying legislative or policy framework has remained largely unchanged; a process Steve Farrell et al have characterised as ‘communicative dissonance’.

Fourth, it is increasingly apparent that ten-years of austerity has become an electoral liability for the Conservative Party and a firm point of difference for Labour.

Decoupling the Conservative brand from its cornerstone economic policy, while maintaining a reputation for fiscal prudence, has proved extremely difficult. In this context investment in ‘frontline services’, such as the police, presents an attractive option for policy-makers seeking to square the circle of post-austerity politics.

Brexit: The ‘elephant in the room’….

Ordinarily these measures – in conjunction with recent announcements on public sector pay and the NHS – might be expected to appeal to the Conservative base and some swing voters. But these are very far from ordinary times. The fate of the current government is inexorably linked to Brexit and this single issue will continue to dominate the political agenda to the exclusion of all else. Europe has accentuated longstanding ideological differences within the Conservative Party (as it has within the Labour movement) and this promoted diametrically opposed positions on how best to respond to the challenges of contemporary statecraft.

The sudden change of direction on penal policy this summer may be the latest manifestation of this conflict, but it is unlikely to be the last.

Thomas Guiney

Lecturer in Criminology at Oxford Brookes.

UK policy now in the hands of a handful of over-priveleged tossers led by country's 'PM' elected by 100,000 Tory party members. Elected chamber clearly not required as Parliament is prorogued to shut down dissenting voices.

ReplyDeleteDemocracy in action; reclaim sovereignty.

10,000 more prison places will just add to the current chaos.

ReplyDeleteUnless Boris and Co haven't noticed the government can't manage the prison estate at its current volume.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/pentonville-prison-jail-violence-self-harm-neglect-moj-london-a9081706.html

https://www.northantstelegraph.co.uk/news/people/union-against-private-running-of-253m-wellingborough-prison-convenes-meeting-1-9050527

DeletePentonville Prison 'overrun' by 'insecticide resistant' cockroaches, watchdog finds

DeleteInsecticide resistant cockroaches have overrun Britain's busiest prison, a watchdog report has found.

HMP Pentonville, in north London, has been “neglected” by the Government resulting “masses of cockroaches” being reported in inmates cells, as well as in the kitchen and visitor areas.

The Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) at HMP Pentonville has called on Robert Buckland MP, Justice Secretary and Lucy Frazer MP, prisons minister, to provide "adequate funds" so improvements can be made "as a matter of urgency".

Despite the number of pest control visits being doubled in January, inspectors noted an infestation of cockroaches has not yet been solved.

While other outbreaks inside the Victorian prison were also reported, including mice in some of the food preparation areas and around a children’s play area in the visitor centre.

Fleas or pigeon mites have also been detected in the prison, along with “biting flies” in one of the showers.

There are around 33,000 "movements" through the category B prison's reception every year - making it the busiest in the country, inspectors previously said.

The IMB said the accommodation, which remains “much as they were when the prison was opened in 1842”, does not generally meet the standards of “humanity, decency or efficiency”, including “squalid” toilets and mouldy showers.

Violence at the prison has also doubled since 2017, against both staff and other prisoners.

In March 2019 four officers and around 40 prisoners were assaulted each week, the report said.

Camilla Poulton, IMB chair, said: “Neither Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) nor the Ministry of Justice have given Pentonville the money, care and scrutiny that it needs for years, in the IMB’s opinion.”

A union that represents prison workers will be holding a meeting about plans for Wellingborough’s new mega-prison next month.

ReplyDeleteThe Public and Commercial Services Union says that rather than the £235m prison currently being built in the town, being run by the private sector as planned, it should be in public ownership.

The prison build has recently come under target by campaigners who are against the government’s expansion of the prison estate and say instead the hundreds of millions should be spent on community services.

The prison – which will showcase a new design – will house up to 1650 prisoners, more than double the number held in the former Wellingborough jail house which was closed in 2012.

HM Prison and Probation Branch Executive Committee member Adam Wissen said: “The closure of HMP Wellingborough was one of a number of small to medium-sized prisons which were closed by the Coalition Government with disastrous consequences for prisoners and staff alike.

Staff were forced out of the job and the community they had often spent a great many years working in. Prisoners were often transferred further away from home, into much larger prisons holding over 1,000 prisoners.

“These prisons were, of course, dealing with the ridiculous budget cuts the Government had foisted upon them, leading to year on year increases in violence, drugs, and self-harm across the prison estate.

“In 2018 it was announced that a new prison would be built on the old site of the closed HMP Wellingborough. In another bizarre twist, it was announced that both of these new prisons would be run by the private sector, the Public Sector Prison Service would not even be allowed to bid to run either of them.

The PCS HMPPS Branch believes there is an urgent debate to be had on the future of prisons, their size, who runs them and what they are used for.

In May 2018 we launched our alternative vision for prisons. We believe that only public ownership and an alternative strategy on re-habilitation can deliver a Prison Service fit for the future and cut re-offending in the community.”

Wellingborough Council leader Martin Griffiths is in favour of the plan and says it will boost the local economy. There will also be skills training centre on-site.

The meeting is being held on Friday, September 13th at the Friends Meeting House in St John’s Street, Wellingborough from 6pm – 8pm.

Speakers include Leader of the Labour Group on Wellingborough Borough Council Cllr Andrew Scarborough, and Andy Baxter from the Prison Officers Union.