It looks as if our new Prime Minister is determined to use all the tricks in the book to ensure he wins the next Election, so we can expect prison numbers to rise and sentence length to increase. A long read even for a Sunday, but this recent forensic report from the Institute for Government has a number of charts that graphically demonstrate the effect of trying to save money on the Prison Service budget. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words:-

Prisons

Prisons have experienced large spending cuts and cuts to staff numbers since 2009/10. Despite promising signs in the early years of this period that this was manageable, in 2013/14 prison safety started to deteriorate sharply. Violence rates have risen, and prisoners appear to have less access to learning and development activities.

Spending has risen recently following an injection of extra cash at the 2016 Autumn Statement to tackle the decline in prison safety. The rate of deaths in prison has subsequently fallen, but the data does not yet show any discernible improvements in overall violence levels.

There are 122 prisons in England and Wales, of which the vast majority (108) are ‘public’ prisons, run directly by Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS). The other 14 (‘private’ prisons) are run by private companies. These tend to be of above-average size, and house 19% of the prison population – up from 15% in 2012/13.*

This chapter looks at all of these prisons, including eight young offender institutions. These young offender institutions accommodate males aged 15–21, although some adult prisons also have youth wings.

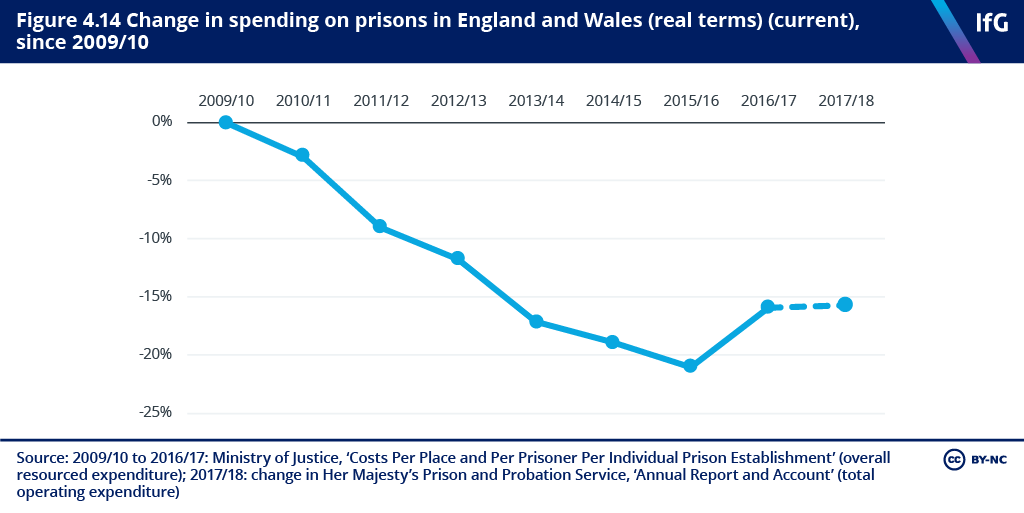

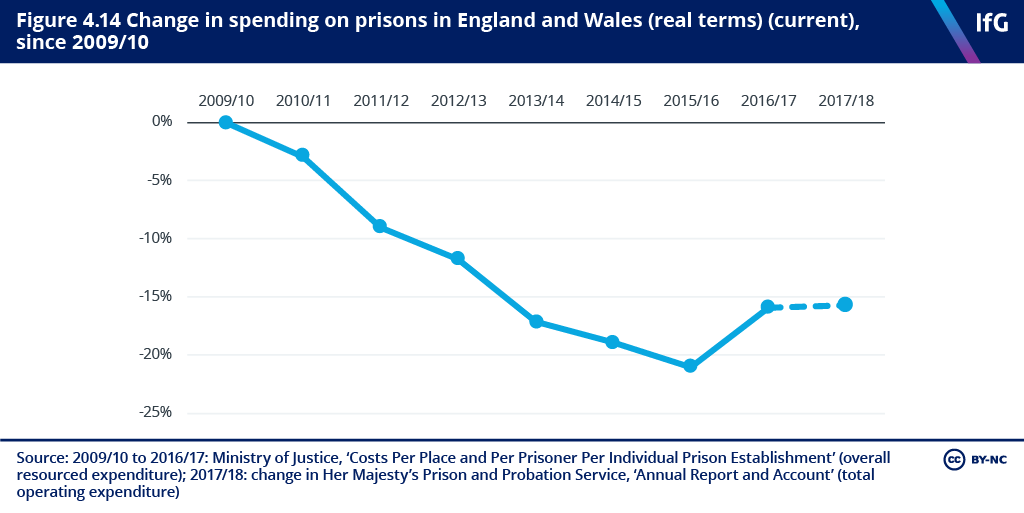

Spending on prisons is 16% lower in real terms than in 2009/10

Between 2009/10 and 2015/16 day-to-day spending on prisons fell sharply – by 21% in real terms – reflecting similarly deep cuts to the wider Ministry of Justice budget. However, extra money was pumped into the prisons budget at the 2016 Autumn Statement – £291 million (m) over three years – to try to tackle the deterioration of safety levels in prisons, most notably by increasing prison officer numbers by 2,500 by the end of 2018. Spending then rose in that year and in 2017/18, around £3 billion was spent on prisons, 16% less than in 2009/10.

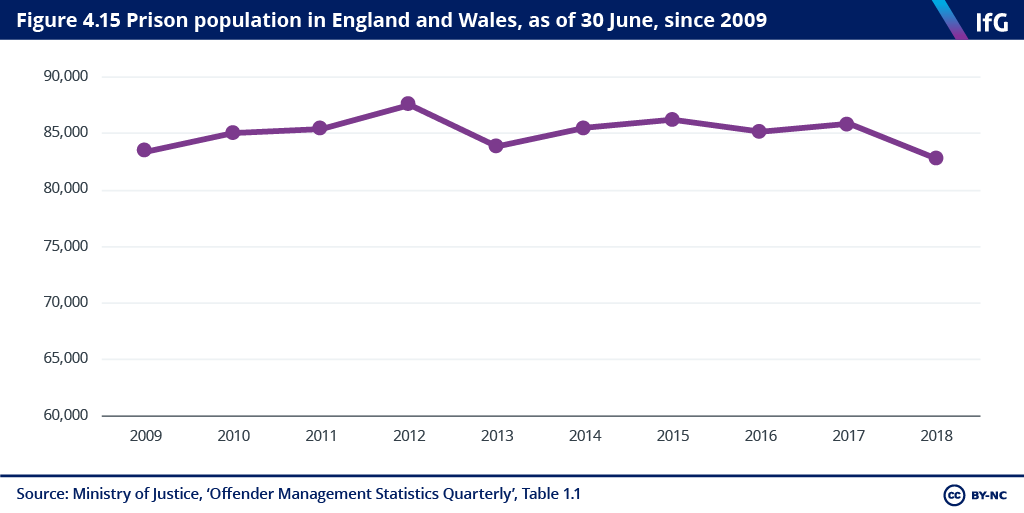

Demand: prisoner numbers have remained broadly flat

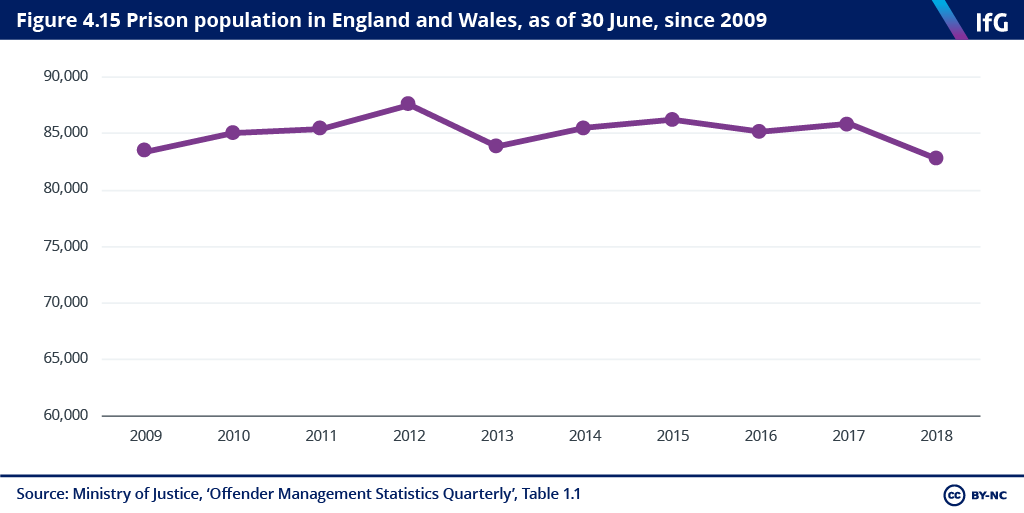

The prison population has remained broadly flat since 2010, in contrast with rapid growth in the 1990s and 2000s. There were 82,773 prisoners in England and Wales on 30 June 2018 compared with 83,391 on 30 June 2009. This shift is in part due to reforms to sentencing in 2008 and a fall in the number of cases being received in the courts.The prison population has remained consistently around 95% male.

The total number of prisoners in June 2018 includes 642 under-18s (all male), most of whom are held in young offender institutions.There has been a dramatic fall over recent years in the number of young people held in custody: between June 2010 and June 2018, the number of under-18s in young offender institutions more than halved (from 1,661 to 642).This reflects an apparent overall fall in youth crime – fewer young people are being cautioned or sentenced. However, there is evidence that the remaining population of young people in custody is becoming more challenging, with a growing proportion being held for violent offences.

Overall, the prison population is ageing: the proportion of the prison population aged under 30 has fallen since 2011 (from 46% to 35% in 2018), while the proportion aged 60 and over has grown (from 4% to 6% in 2018). Within this there has been a rise in the number of prisoners in the oldest age bracket – a 16% rise in the number of people aged 70 and over in prison over the past two years – which signals potential rising care needs in the prison population.

Data on the prevalence of mental illness in prisons is incomplete, but estimates range from 23% (of a sample of prisoners who reported previous contact with mental health services) to 37% (of prisoners surveyed by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons – HMIP – in 2016/17 who reported having an emotional wellbeing or mental health problem).This indicates that the prevalence of mental health issues may be higher among prisoners than the general population (estimated in 2007 to be around 23%) – although we do not know how the prevalence of mental health problems in prisons has changed over time.

There are also signs that an influx of new types of drugs – called ‘new psychoactive substances’ – is putting new pressures on prisons. New psychoactive substances – such as ‘Spice’ – are synthetically produced drugs, originally designed to mimic the effects of illegal substances (although they are now themselves illegal). They can cause aggression, psychosis and intense depressive episodes. In 2016, the prison and probation ombudsman described them as a ‘game-changer’ for prison safety.

Screening for the use of new psychoactive substances in prisons was first introduced in 2016. Since then, one year of data has been published, showing that they are by far the most prevalently used drugs in prisons: in 2017/18, 10.1% of mandatory drug tests were positive for their use, compared with a 10.3% positive drug test for all other drugs.

Input: the number of prisons has fallen – but prison capacity remains the same

There are 122 prisons in England and Wales, down from 137 in 2009/10. Since 2009/10, 20 prisons have closed or merged, and five new prisons have opened. However, despite a fall in the number of prisons, the overall capacity of the prison system was roughly the same at the end of 2017/18 as at the end of 2009/10, due to the larger size of the new prisons.

Only one brand new prison has been initiated and built since 2009/10: Berwyn, in North Wales. Originally announced in 2013, it began to receive prisoners in February 2017.

Two of the prisons opened since 2009/10 are privately operated: one (Thameside in London) operates under a Private Finance Initiative (PFI) contract, meaning that it was both built and is now run by a private company; the other (Oakwood in Staffordshire) was built by the public sector but is run by G4S. Another of these new prisons (Northumberland) was originally opened as a public prison in 2011 but was taken over by G4S in 2013. At the same time, G4S also took over Birmingham prison – previously a publicly run prison.

Just one prison has reverted from private to public management during this period: Wolds prison in Yorkshire, which had been run by G4S from when it opened in 1991, but was brought under public management in 2013 (following a critical inspection report and G4S’s high-profile failure at the 2012 Olympics) when the previous PFI deal ran out.*

* Wolds was merged with publicly run Everthorpe prison to form Humber prison

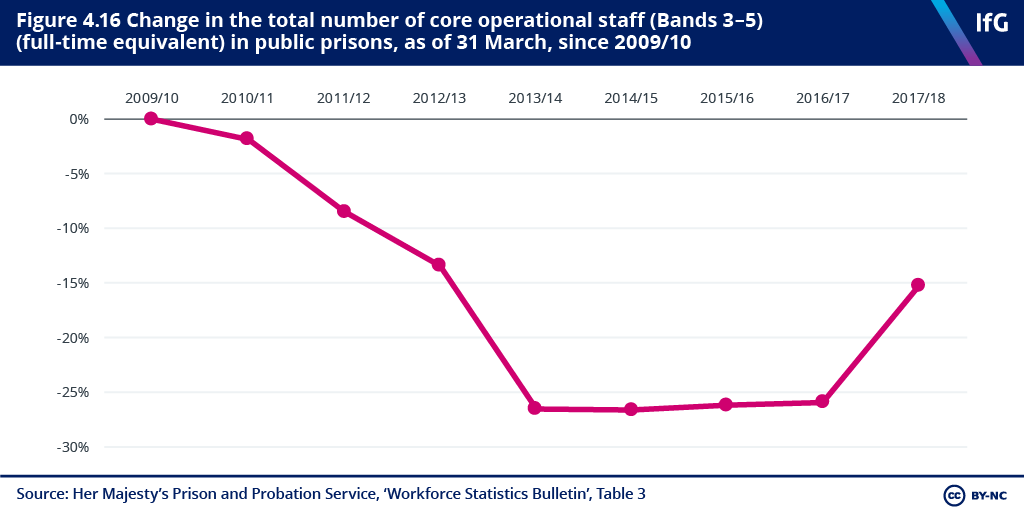

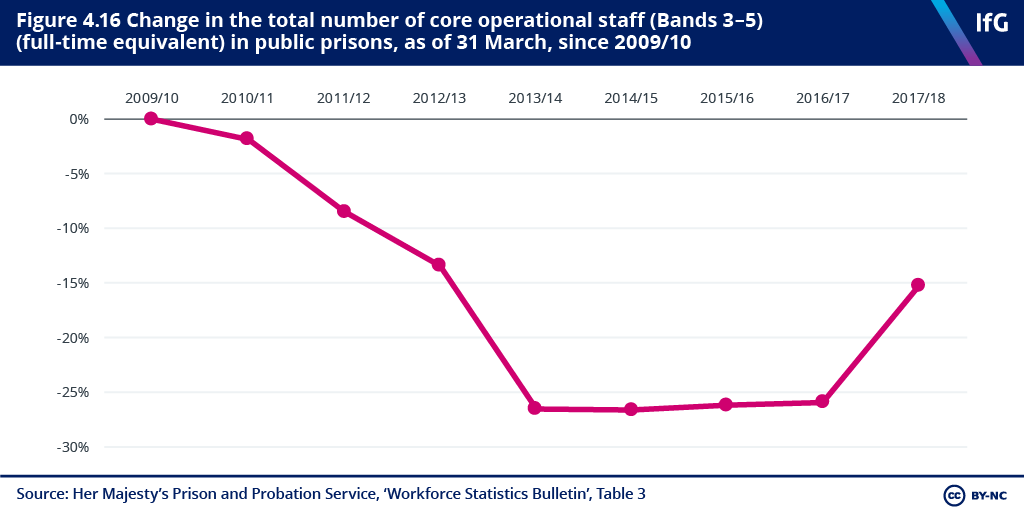

Input: staff numbers in public prisons are starting to rise again, following deep cuts

Prisons’ main strategy for dealing with budget cuts has been to reduce staff numbers. Across the whole prison estate, around 40% of spending went on staff costs in 2016/17 – down from 48% in 2012/13 (the earliest year for which we have comparable data). That equates to a 21% real-terms decrease in spending on staff over that period.[

Below is an analysis of what has happened to the public prison workforce. No information is publicly available on what has happened to staffing levels in private prisons.

Since March 2017, the number of prison officers has risen by 3,205 – a 17% increase. At the end of the 2017/18 financial year, there were 21,041 full-time equivalent (FTE) prison officers in public prisons in England and Wales – rising further to 21,608 in June 2018. This follows a large decline – of 26%, or 6,580 officers – between 2009/10 and 2013/14. This means that the Government has not only met its target (set at the end of 2016) of recruiting an extra 2,500 prison officers by the end of 2018, it has exceeded it.

This is the net increase – the actual level of recruitment into the prison service in 2016/17 was much higher. This has been key to meeting the Government’s recruitment target, as the retention rate for prison officers is low. In 2016/17, 4,933 new prison officers joined the prison service, while 2,088 left. If turnover continues at this rate – or worsens – HMPPS will be faced with the task of recruiting thousands of new prison officers every year, just to keep numbers steady.

This high turnover means that, even though there are now almost as many prison officers as there were five years ago, the composition of prison staff is different.

Experience levels have fallen. In June 2018 a third of prison officers had less than two years’ experience (compared with 7% in March 2010); 49% had experience of 10 years (down from 56% in 2009/10). While many of those individuals may well be competent and skilled, the overall decline in experience may have had a negative impact on the overall effectiveness of the workforce.** The Prison Service Pay Review Body has raised concern about the high levels of inexperience in the prison service, citing in particular the extra burden on longstanding officers to mentor new recruits.

Although the number of prison officers has started to grow, other parts of the prison workforce have continued to shrink. The number of prison managers has fallen consistently over the past eight years, from 1,434 in March 2010 to 905 in June 2018 (a 37% decrease).

** For example, HMIP concluded that the “inexperience of many staff” underpinned the problems it encountered at Nottingham prison in January 2018, where conditions were so poor that an ‘Urgent Notice’ was invoked, making the Secretary of State directly accountable for improving performance. See HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, Report on an Unannounced Inspection of HMP and YOI Nottingham, HM Inspectorate of Prisons, May 2018.

Output: prison safety has continued to decline

The essential activity of prisons is to hold prisoners in custody – to stop them escaping. On this count, performance has been good over the past eight years. Between 2009/10 and 2017/18 there were no more than two escapes a year (where a prisoner has to physically overcome some restraint or barrier to go out of the control of the staff) – except in 2016/17 when there were four. The number of absconders – prisoners who escaped from an open environment – fell steadily, from 269 in 2009/10 to 86 in 2016/17 (while the number of prisoners in open prisons rose). However, in 2017/18 the number rose again to 139.

But the work of prisons transcends just keeping people inside. We expect prisoners to be kept healthy and safe. It is also the Government’s stated intention that prisons should play a role in preparing prisoners for a life outside of prison – the ‘rehabilitation revolution’ hailed by former Justice Secretary Chris Grayling. However, the evidence suggests that prisons are struggling on all of those counts.

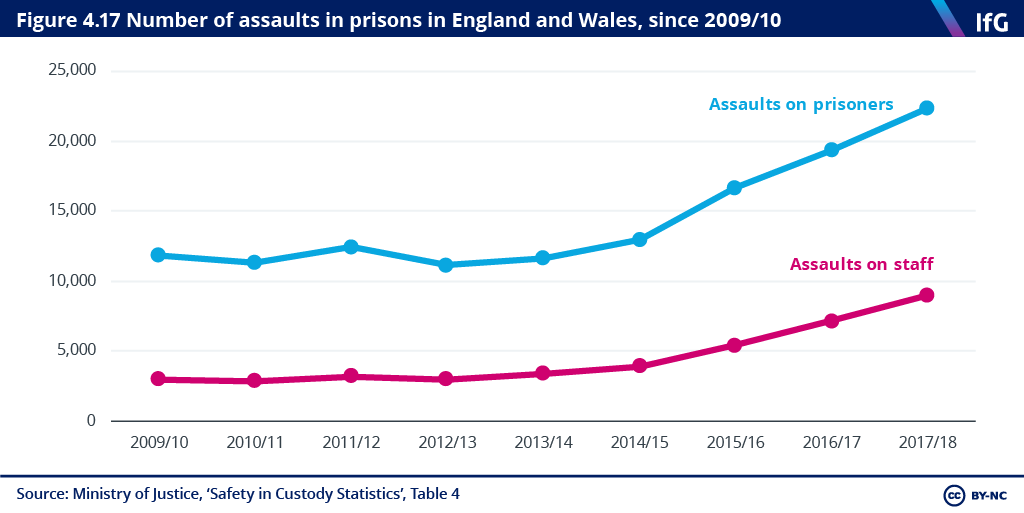

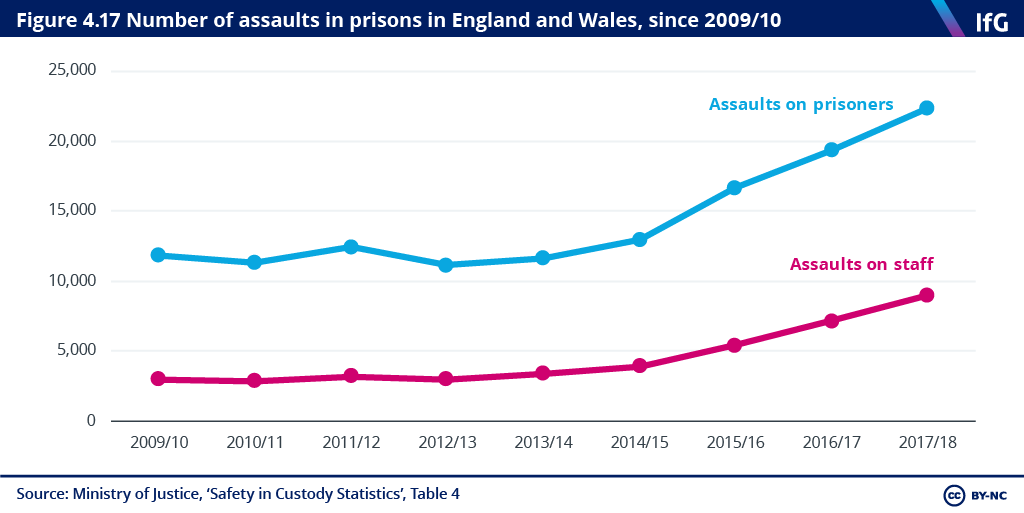

Output: prison violence continues to intensify...

Prisons have continued to become more dangerous for both staff and prisoners over the past year. In 2017/18 there were more than 9,000 assaults on prison staff (or 106 for every 1,000 prisoners). That means the frequency of assaults has almost tripled since 2009/10 – in both raw and per-prisoner terms. There was a 26% increase (from 7,159) in the past year alone. The frequency of serious assaults against staff has risen even faster – from 289 (or three for every 1,000 prisoners) in 2009/10 to 892 (or 10 for every 1,000 prisoners) in 2017/18.

Assaults on prisoners by other prisoners are much more frequent than assaults on staff. There were 22,374 prisoner-on-prisoner assaults in 2017/18 – nearly double the number that took place in 2009/10. That works out as 262 assaults per 1,000 prisoners – up from 142 in 2009/10. Serious assaults against prisoners rose even more rapidly: from 1,087 to 3,081.

These figures are themselves likely to be an underestimation of the actual number of assaults: a government audit of data collection practices in prisons this year found that assaults were underreported by 10% last year. So the actual number of assaults was probably even higher.

A number of things could have caused this serious increase in prison violence. It could be directly related to the pace of prison staff reduction. In 2013/14 alone, prison officer numbers fell by 15% (or 3,250 officers) – equalling the reductions seen in total over the previous four years. It may be that those previous reductions were sustainable, but that the 2013/14 staff cuts went too far. There may have been a ‘lagged’ effect, with problems caused by earlier staff reductions taking a while to show up in the data. The presence of new psychoactive substances has also clearly been a factor: due to both the violent effects induced by the drugs themselves, and also to violence associated with dealing and supply. A recent evidence review commissioned by the Ministry of Justice found that “the crucial factor in maintaining order is the availability and the skills of unit staff”.

Rates of violence among youth offenders are far higher than among the adult population. Across the whole ‘youth estate’ – including all 15- to 17-year-olds, not just those in young offender institutions – there were 2.77 assaults per prisoner in 2017/18, up from 1.84 in 2012/13 (the earliest year with comparable data). This, of course, has happened at the same time as the size of the youth estate has shrunk rapidly.

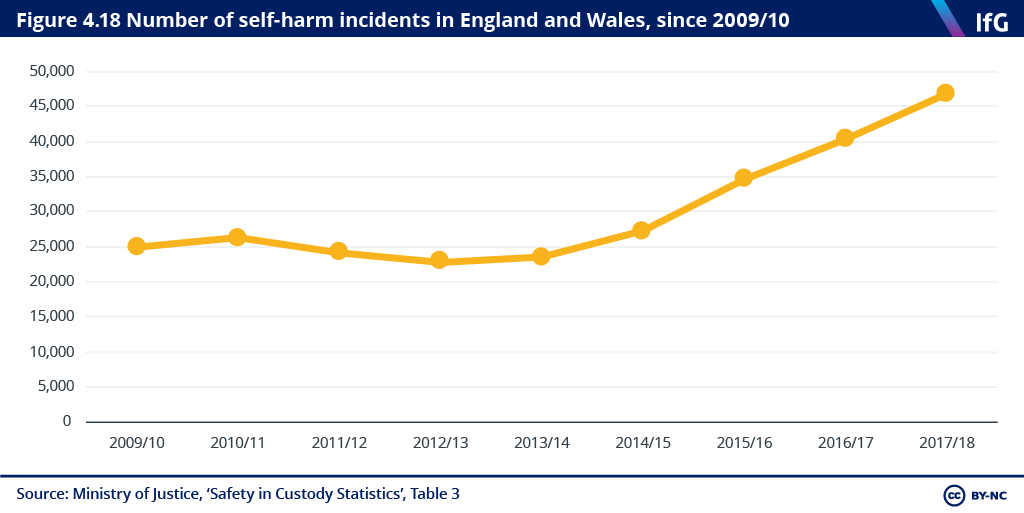

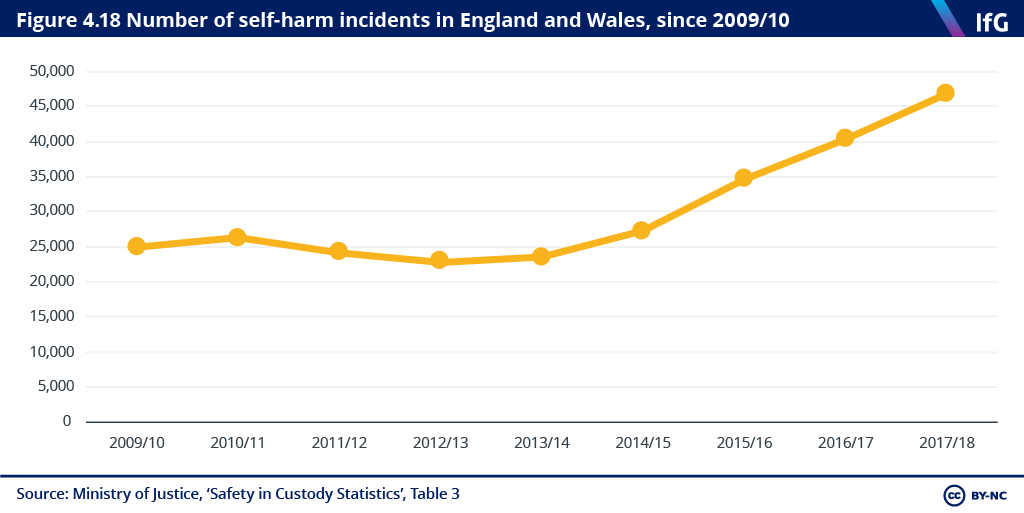

…and prisoners are self-harming with increasing frequency

Prisoners are also harming themselves with increasing frequency. The number of self-harm incidents rose by 88% (from just under 25,000 to just under 47,000) between 2009/10 and 2017/18. These incidents were gendered: there were 2,244 self-harm incidents for every 1,000 female prisoners, compared with 467 for every 1,000 male prisoners. The gender differential was much smaller among assault incidents: there were 366 assaults for every 1,000 male prisoners in 2017/18 and 318 for every 1,000 female prisoners.

One indicator is improving, however. Self-inflicted deaths in prison fell in 2017/18 to their lowest levels since 2012/13, after a big increase in 2015/16 and 2016/17. However, that still amounted to 69 self-inflicted deaths in prison in 2017/18 (0.8 for every 1,000 prisoners).

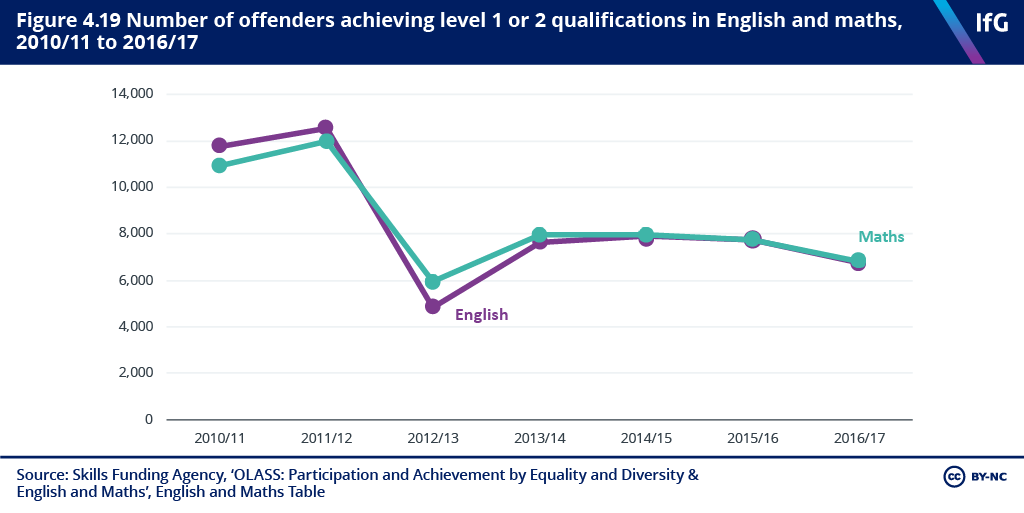

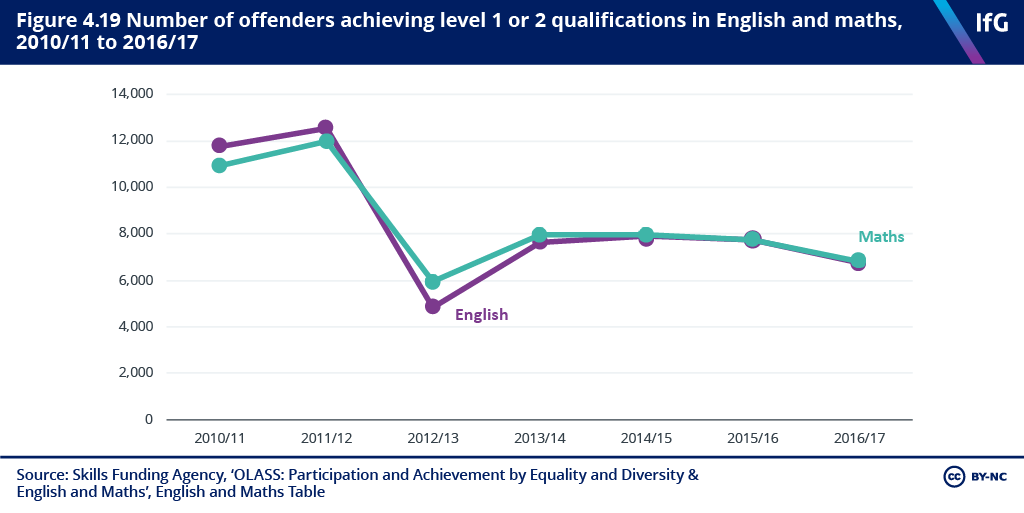

Output: prisoners’ access to rehabilitative activity appears to be worsening

The evidence on what prisoners do with their time – and how much access they have to activities that might support their rehabilitation and wellbeing – is limited. The Ministry of Justice stopped publishing data on the number of hours that prisoners spent “engaged in purposeful activity” (such as education or training) in 2011/12 – although, up to that point, average hours were rising.

There are concerns that the issues outlined above – a shrinking workforce and a violent environment – are limiting prisoners’ opportunities to engage in meaningful activity, by increasing the time they spend locked in their cells. In its 2017/18 survey, HMIP found that only 16% of prisoners were unlocked for the recommended 10 hours a day. We have no consistent data on how this has changed over time.

What we do know is that fewer prisoners appear to be starting and completing accredited courses that may support them on their release from prison. The number of prisoners completing ‘accredited programmes’, largely designed to support behaviour change and improve thinking skills, has fallen by 22% since 2014/15 (from 6,994 to 5,479). We have excluded ‘accredited substance misuse programmes’ from this analysis because responsibility for funding and commissioning all substance misuse treatment in prison was transferred to the NHS in 2013. There may be other cases within our figures where other activity has replaced formally ‘accredited’ programmes, accounting for some of the decline.

But there have been no such changes in the definition of academic qualifications. Here we can observe a clear decline. In 2016/17, 6,750 prisoners achieved a level 1 or 2 (pre-GCSE and GCSE-level) qualification in English, down from 11,760 in 2010/11 (a 43% decline). Similarly, the number achieving a level 1 or 2 qualification in maths fell from 10,950 to 6,800 (a 38% decline).

Have prisons become more efficient and can that be maintained?

In 2010, former Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke accepted large cuts to his departmental budget. This was on the understanding that the Government would bring forward legislation to reform sentencing and reduce the size of the prison population.

However, plans to introduce sentencing ‘discounts’ for early guilty pleas were scrapped in 2011, in the midst of political controversy over their potential application to rapists. At a press conference to announce this change, of course, then-Prime Minister David Cameron said the gap would be made up instead through ‘greater efficiency’.

As with most other services examined in Performance Tracker, economies were made in prisons through the pay cap: pay was frozen between 2011/12 and 2012/13, and increases were subsequently capped at 1% a year. But prison officers were among the first public servants to see their pay cap broken. In September 2017, they received a 1.7% pay rise for the 2017/18 financial year – and have been awarded a 2.75% increase for 2018/19.

Pay has not apparently been a barrier to recruiting the extra prison officers needed for the Ministry of Justice to meet its 2016 target of increasing prison officer numbers by 2,500 by the end of 2018. However, it may have contributed to the growing retention problem. High turnover will not necessarily be disastrous for the service, if it can continue recruiting at the rate it has this year. But continually replacing staff is of course much less efficient than holding on to them.

Another high-profile attempt at making economies was through the outsourcing of the maintenance contract in public prisons to Carillion and Amey in 2014 – large private contractors that promised to deliver the service at a much reduced cost. However, since the collapse of Carillion at the start of 2018, it has become clear that the outsourcers had seriously underbid, underestimating the scale of the task involved. The National Audit Office has estimated that Carillion was operating at a loss of around £12m on these contracts in 2017. The Carillion contracts have now reverted to a new ‘government-owned company’, which is receiving an extra £15m a year to provide an adequate service.

Since 2015, the Government’s key set of efficiency reforms have focused on creating new prison places. The 2015 Spending Review promised 10,000 new prison places – and four new prisons – by 2020, with five new prisons due after that. Estimated savings were £80m a year. However, these savings will not yet have been released: planning permission has been granted for three new prisons, but construction has not yet begun.

There are likely to have been productivity gains in some parts of the prison service. As far as we can tell (the unseen numbers for private prisons may complicate this picture), fewer prison officers are overseeing more prisoners – at this basic level, prisons are achieving more ‘output’ for each unit of ‘input’. There are indications, too, that those prisoners are becoming more challenging to oversee – with the rise of new drugs of particular concern.

One clear example we have is the ‘send money to someone in prison’ online service, which went live in 2017/18. By halving transaction costs, this is projected to save £17m over five years. A handful of sites have acted as ‘digital prison’ pilots – giving prisoners in-cell access to online services allowing them to make their meal choices, or make orders from the prison shop. But these are small-scale – and we do not know what size of savings they may have made.

Our ability to make a clear judgement on efficiency gains in prisons is hampered by the lack of data on private prisons – specifically, the lack of staff data. It is also difficult to discern what has happened to non-staff prison spending, such as catering and maintenance. However, given the scale of the deterioration in quality in both public and private prisons over the past five years, we cannot conclude that the service has become more efficient overall. This is particularly true of the past year – when spending and staff numbers rose, but violence and self-harm incidents continued to increase in frequency.

Although spending on prisons has risen, it remains 16% below the level in 2009/10 – meaning that it remains important for the prison service to maintain any genuine productivity improvements it has managed to produce. However, the more important question will be whether that extra investment is successfully used to produce an acceptable level of performance, particularly with regard to prison safety.

Have efficiencies been enough to meet demand?

The Government has more power to control the demand on prisons than for many other services examined in this report – by legislating to change the length and types of sentences that different types of offence and offender attract. But while there have been changes to legislation and guidelines around sentencing over the period since 2009/10, most of them involve increasing the use of custodial sentences or lengthening them: for example, the minimum term of a life sentence for murder with a knife was raised from 15 to 25 years in 2010, while the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015 restricted the use of cautions.

In the case of prisons, the answer to the question of whether efficiencies have been enough to meet demand is a straightforward ‘no’. Any efficiency improvements that may have been made in parts of the system have been swamped by other demands, leading to a decline in quality, indicated by rising violence. Whether or not new drugs have been the key driver of rising violence, their presence has clearly amplified the challenges the prison system has faced in managing within a tightened budget.

This is particularly true after 2012/13. Before that point, there is evidence that efficiency improvements may have made up for falling spending: spending fell by 17% while prisoner numbers fell by only 5% between 2009/10 and 2012/13, but levels of violence and self-harm remained broadly flat. After that point, however, violence and self-harm rates began to increase – a trend that continues.

Demand: prisoner numbers have remained broadly flat

The prison population has remained broadly flat since 2010, in contrast with rapid growth in the 1990s and 2000s. There were 82,773 prisoners in England and Wales on 30 June 2018 compared with 83,391 on 30 June 2009. This shift is in part due to reforms to sentencing in 2008 and a fall in the number of cases being received in the courts.The prison population has remained consistently around 95% male.

The total number of prisoners in June 2018 includes 642 under-18s (all male), most of whom are held in young offender institutions.There has been a dramatic fall over recent years in the number of young people held in custody: between June 2010 and June 2018, the number of under-18s in young offender institutions more than halved (from 1,661 to 642).This reflects an apparent overall fall in youth crime – fewer young people are being cautioned or sentenced. However, there is evidence that the remaining population of young people in custody is becoming more challenging, with a growing proportion being held for violent offences.

Overall, the prison population is ageing: the proportion of the prison population aged under 30 has fallen since 2011 (from 46% to 35% in 2018), while the proportion aged 60 and over has grown (from 4% to 6% in 2018). Within this there has been a rise in the number of prisoners in the oldest age bracket – a 16% rise in the number of people aged 70 and over in prison over the past two years – which signals potential rising care needs in the prison population.

Data on the prevalence of mental illness in prisons is incomplete, but estimates range from 23% (of a sample of prisoners who reported previous contact with mental health services) to 37% (of prisoners surveyed by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons – HMIP – in 2016/17 who reported having an emotional wellbeing or mental health problem).This indicates that the prevalence of mental health issues may be higher among prisoners than the general population (estimated in 2007 to be around 23%) – although we do not know how the prevalence of mental health problems in prisons has changed over time.

There are also signs that an influx of new types of drugs – called ‘new psychoactive substances’ – is putting new pressures on prisons. New psychoactive substances – such as ‘Spice’ – are synthetically produced drugs, originally designed to mimic the effects of illegal substances (although they are now themselves illegal). They can cause aggression, psychosis and intense depressive episodes. In 2016, the prison and probation ombudsman described them as a ‘game-changer’ for prison safety.

Screening for the use of new psychoactive substances in prisons was first introduced in 2016. Since then, one year of data has been published, showing that they are by far the most prevalently used drugs in prisons: in 2017/18, 10.1% of mandatory drug tests were positive for their use, compared with a 10.3% positive drug test for all other drugs.

Input: the number of prisons has fallen – but prison capacity remains the same

There are 122 prisons in England and Wales, down from 137 in 2009/10. Since 2009/10, 20 prisons have closed or merged, and five new prisons have opened. However, despite a fall in the number of prisons, the overall capacity of the prison system was roughly the same at the end of 2017/18 as at the end of 2009/10, due to the larger size of the new prisons.

Only one brand new prison has been initiated and built since 2009/10: Berwyn, in North Wales. Originally announced in 2013, it began to receive prisoners in February 2017.

Two of the prisons opened since 2009/10 are privately operated: one (Thameside in London) operates under a Private Finance Initiative (PFI) contract, meaning that it was both built and is now run by a private company; the other (Oakwood in Staffordshire) was built by the public sector but is run by G4S. Another of these new prisons (Northumberland) was originally opened as a public prison in 2011 but was taken over by G4S in 2013. At the same time, G4S also took over Birmingham prison – previously a publicly run prison.

Just one prison has reverted from private to public management during this period: Wolds prison in Yorkshire, which had been run by G4S from when it opened in 1991, but was brought under public management in 2013 (following a critical inspection report and G4S’s high-profile failure at the 2012 Olympics) when the previous PFI deal ran out.*

* Wolds was merged with publicly run Everthorpe prison to form Humber prison

Input: staff numbers in public prisons are starting to rise again, following deep cuts

Prisons’ main strategy for dealing with budget cuts has been to reduce staff numbers. Across the whole prison estate, around 40% of spending went on staff costs in 2016/17 – down from 48% in 2012/13 (the earliest year for which we have comparable data). That equates to a 21% real-terms decrease in spending on staff over that period.[

Below is an analysis of what has happened to the public prison workforce. No information is publicly available on what has happened to staffing levels in private prisons.

Since March 2017, the number of prison officers has risen by 3,205 – a 17% increase. At the end of the 2017/18 financial year, there were 21,041 full-time equivalent (FTE) prison officers in public prisons in England and Wales – rising further to 21,608 in June 2018. This follows a large decline – of 26%, or 6,580 officers – between 2009/10 and 2013/14. This means that the Government has not only met its target (set at the end of 2016) of recruiting an extra 2,500 prison officers by the end of 2018, it has exceeded it.

This is the net increase – the actual level of recruitment into the prison service in 2016/17 was much higher. This has been key to meeting the Government’s recruitment target, as the retention rate for prison officers is low. In 2016/17, 4,933 new prison officers joined the prison service, while 2,088 left. If turnover continues at this rate – or worsens – HMPPS will be faced with the task of recruiting thousands of new prison officers every year, just to keep numbers steady.

This high turnover means that, even though there are now almost as many prison officers as there were five years ago, the composition of prison staff is different.

Experience levels have fallen. In June 2018 a third of prison officers had less than two years’ experience (compared with 7% in March 2010); 49% had experience of 10 years (down from 56% in 2009/10). While many of those individuals may well be competent and skilled, the overall decline in experience may have had a negative impact on the overall effectiveness of the workforce.** The Prison Service Pay Review Body has raised concern about the high levels of inexperience in the prison service, citing in particular the extra burden on longstanding officers to mentor new recruits.

Although the number of prison officers has started to grow, other parts of the prison workforce have continued to shrink. The number of prison managers has fallen consistently over the past eight years, from 1,434 in March 2010 to 905 in June 2018 (a 37% decrease).

** For example, HMIP concluded that the “inexperience of many staff” underpinned the problems it encountered at Nottingham prison in January 2018, where conditions were so poor that an ‘Urgent Notice’ was invoked, making the Secretary of State directly accountable for improving performance. See HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, Report on an Unannounced Inspection of HMP and YOI Nottingham, HM Inspectorate of Prisons, May 2018.

Output: prison safety has continued to decline

The essential activity of prisons is to hold prisoners in custody – to stop them escaping. On this count, performance has been good over the past eight years. Between 2009/10 and 2017/18 there were no more than two escapes a year (where a prisoner has to physically overcome some restraint or barrier to go out of the control of the staff) – except in 2016/17 when there were four. The number of absconders – prisoners who escaped from an open environment – fell steadily, from 269 in 2009/10 to 86 in 2016/17 (while the number of prisoners in open prisons rose). However, in 2017/18 the number rose again to 139.

But the work of prisons transcends just keeping people inside. We expect prisoners to be kept healthy and safe. It is also the Government’s stated intention that prisons should play a role in preparing prisoners for a life outside of prison – the ‘rehabilitation revolution’ hailed by former Justice Secretary Chris Grayling. However, the evidence suggests that prisons are struggling on all of those counts.

Output: prison violence continues to intensify...

Prisons have continued to become more dangerous for both staff and prisoners over the past year. In 2017/18 there were more than 9,000 assaults on prison staff (or 106 for every 1,000 prisoners). That means the frequency of assaults has almost tripled since 2009/10 – in both raw and per-prisoner terms. There was a 26% increase (from 7,159) in the past year alone. The frequency of serious assaults against staff has risen even faster – from 289 (or three for every 1,000 prisoners) in 2009/10 to 892 (or 10 for every 1,000 prisoners) in 2017/18.

Assaults on prisoners by other prisoners are much more frequent than assaults on staff. There were 22,374 prisoner-on-prisoner assaults in 2017/18 – nearly double the number that took place in 2009/10. That works out as 262 assaults per 1,000 prisoners – up from 142 in 2009/10. Serious assaults against prisoners rose even more rapidly: from 1,087 to 3,081.

These figures are themselves likely to be an underestimation of the actual number of assaults: a government audit of data collection practices in prisons this year found that assaults were underreported by 10% last year. So the actual number of assaults was probably even higher.

A number of things could have caused this serious increase in prison violence. It could be directly related to the pace of prison staff reduction. In 2013/14 alone, prison officer numbers fell by 15% (or 3,250 officers) – equalling the reductions seen in total over the previous four years. It may be that those previous reductions were sustainable, but that the 2013/14 staff cuts went too far. There may have been a ‘lagged’ effect, with problems caused by earlier staff reductions taking a while to show up in the data. The presence of new psychoactive substances has also clearly been a factor: due to both the violent effects induced by the drugs themselves, and also to violence associated with dealing and supply. A recent evidence review commissioned by the Ministry of Justice found that “the crucial factor in maintaining order is the availability and the skills of unit staff”.

Rates of violence among youth offenders are far higher than among the adult population. Across the whole ‘youth estate’ – including all 15- to 17-year-olds, not just those in young offender institutions – there were 2.77 assaults per prisoner in 2017/18, up from 1.84 in 2012/13 (the earliest year with comparable data). This, of course, has happened at the same time as the size of the youth estate has shrunk rapidly.

…and prisoners are self-harming with increasing frequency

Prisoners are also harming themselves with increasing frequency. The number of self-harm incidents rose by 88% (from just under 25,000 to just under 47,000) between 2009/10 and 2017/18. These incidents were gendered: there were 2,244 self-harm incidents for every 1,000 female prisoners, compared with 467 for every 1,000 male prisoners. The gender differential was much smaller among assault incidents: there were 366 assaults for every 1,000 male prisoners in 2017/18 and 318 for every 1,000 female prisoners.

One indicator is improving, however. Self-inflicted deaths in prison fell in 2017/18 to their lowest levels since 2012/13, after a big increase in 2015/16 and 2016/17. However, that still amounted to 69 self-inflicted deaths in prison in 2017/18 (0.8 for every 1,000 prisoners).

Output: prisoners’ access to rehabilitative activity appears to be worsening

The evidence on what prisoners do with their time – and how much access they have to activities that might support their rehabilitation and wellbeing – is limited. The Ministry of Justice stopped publishing data on the number of hours that prisoners spent “engaged in purposeful activity” (such as education or training) in 2011/12 – although, up to that point, average hours were rising.

There are concerns that the issues outlined above – a shrinking workforce and a violent environment – are limiting prisoners’ opportunities to engage in meaningful activity, by increasing the time they spend locked in their cells. In its 2017/18 survey, HMIP found that only 16% of prisoners were unlocked for the recommended 10 hours a day. We have no consistent data on how this has changed over time.

What we do know is that fewer prisoners appear to be starting and completing accredited courses that may support them on their release from prison. The number of prisoners completing ‘accredited programmes’, largely designed to support behaviour change and improve thinking skills, has fallen by 22% since 2014/15 (from 6,994 to 5,479). We have excluded ‘accredited substance misuse programmes’ from this analysis because responsibility for funding and commissioning all substance misuse treatment in prison was transferred to the NHS in 2013. There may be other cases within our figures where other activity has replaced formally ‘accredited’ programmes, accounting for some of the decline.

But there have been no such changes in the definition of academic qualifications. Here we can observe a clear decline. In 2016/17, 6,750 prisoners achieved a level 1 or 2 (pre-GCSE and GCSE-level) qualification in English, down from 11,760 in 2010/11 (a 43% decline). Similarly, the number achieving a level 1 or 2 qualification in maths fell from 10,950 to 6,800 (a 38% decline).

Have prisons become more efficient and can that be maintained?

In 2010, former Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke accepted large cuts to his departmental budget. This was on the understanding that the Government would bring forward legislation to reform sentencing and reduce the size of the prison population.

However, plans to introduce sentencing ‘discounts’ for early guilty pleas were scrapped in 2011, in the midst of political controversy over their potential application to rapists. At a press conference to announce this change, of course, then-Prime Minister David Cameron said the gap would be made up instead through ‘greater efficiency’.

As with most other services examined in Performance Tracker, economies were made in prisons through the pay cap: pay was frozen between 2011/12 and 2012/13, and increases were subsequently capped at 1% a year. But prison officers were among the first public servants to see their pay cap broken. In September 2017, they received a 1.7% pay rise for the 2017/18 financial year – and have been awarded a 2.75% increase for 2018/19.

Pay has not apparently been a barrier to recruiting the extra prison officers needed for the Ministry of Justice to meet its 2016 target of increasing prison officer numbers by 2,500 by the end of 2018. However, it may have contributed to the growing retention problem. High turnover will not necessarily be disastrous for the service, if it can continue recruiting at the rate it has this year. But continually replacing staff is of course much less efficient than holding on to them.

Another high-profile attempt at making economies was through the outsourcing of the maintenance contract in public prisons to Carillion and Amey in 2014 – large private contractors that promised to deliver the service at a much reduced cost. However, since the collapse of Carillion at the start of 2018, it has become clear that the outsourcers had seriously underbid, underestimating the scale of the task involved. The National Audit Office has estimated that Carillion was operating at a loss of around £12m on these contracts in 2017. The Carillion contracts have now reverted to a new ‘government-owned company’, which is receiving an extra £15m a year to provide an adequate service.

Since 2015, the Government’s key set of efficiency reforms have focused on creating new prison places. The 2015 Spending Review promised 10,000 new prison places – and four new prisons – by 2020, with five new prisons due after that. Estimated savings were £80m a year. However, these savings will not yet have been released: planning permission has been granted for three new prisons, but construction has not yet begun.

There are likely to have been productivity gains in some parts of the prison service. As far as we can tell (the unseen numbers for private prisons may complicate this picture), fewer prison officers are overseeing more prisoners – at this basic level, prisons are achieving more ‘output’ for each unit of ‘input’. There are indications, too, that those prisoners are becoming more challenging to oversee – with the rise of new drugs of particular concern.

One clear example we have is the ‘send money to someone in prison’ online service, which went live in 2017/18. By halving transaction costs, this is projected to save £17m over five years. A handful of sites have acted as ‘digital prison’ pilots – giving prisoners in-cell access to online services allowing them to make their meal choices, or make orders from the prison shop. But these are small-scale – and we do not know what size of savings they may have made.

Our ability to make a clear judgement on efficiency gains in prisons is hampered by the lack of data on private prisons – specifically, the lack of staff data. It is also difficult to discern what has happened to non-staff prison spending, such as catering and maintenance. However, given the scale of the deterioration in quality in both public and private prisons over the past five years, we cannot conclude that the service has become more efficient overall. This is particularly true of the past year – when spending and staff numbers rose, but violence and self-harm incidents continued to increase in frequency.

Although spending on prisons has risen, it remains 16% below the level in 2009/10 – meaning that it remains important for the prison service to maintain any genuine productivity improvements it has managed to produce. However, the more important question will be whether that extra investment is successfully used to produce an acceptable level of performance, particularly with regard to prison safety.

Have efficiencies been enough to meet demand?

The Government has more power to control the demand on prisons than for many other services examined in this report – by legislating to change the length and types of sentences that different types of offence and offender attract. But while there have been changes to legislation and guidelines around sentencing over the period since 2009/10, most of them involve increasing the use of custodial sentences or lengthening them: for example, the minimum term of a life sentence for murder with a knife was raised from 15 to 25 years in 2010, while the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015 restricted the use of cautions.

In the case of prisons, the answer to the question of whether efficiencies have been enough to meet demand is a straightforward ‘no’. Any efficiency improvements that may have been made in parts of the system have been swamped by other demands, leading to a decline in quality, indicated by rising violence. Whether or not new drugs have been the key driver of rising violence, their presence has clearly amplified the challenges the prison system has faced in managing within a tightened budget.

This is particularly true after 2012/13. Before that point, there is evidence that efficiency improvements may have made up for falling spending: spending fell by 17% while prisoner numbers fell by only 5% between 2009/10 and 2012/13, but levels of violence and self-harm remained broadly flat. After that point, however, violence and self-harm rates began to increase – a trend that continues.

https://www.newsandstar.co.uk/news/17815040.prison-days-really-paradise---hell-earth/

ReplyDeleteNew upw supervisors being trained by supervisors that haven’t even finished there 3 month trial period . Yes folks the public are in safe hands. The management should be ashamed .

ReplyDeleteThe roots of the problems being faced by prisons today are sown in the communities the people being sent to prison come from.

ReplyDeleteGrowing homelessness and poverty, housing crisis and savage cuts to local services all done in the name of austerity have changed our communities terribly. Welfare cuts and universal credit have forced many people into doing more insecure jobs, often hopping from job to job to make ends meet. More hours at work mean less hours spent with the kids.

If our communities are becoming more feral, then that's obviously going to be reflected in our penal system.

Yet there's no real incentive for politicians to solve any of these issues. It is after all the promise to fix our broken communities and social structures that gets them elected. If they fixed it all they'd have nothing to promise people when elections come around.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/children-prison-special-educational-needs-jail-uk-a9034846.html

'Getafix

Could be a thousand words paints a picture?

Deletehttps://insidetime.org/getting-it-right/

I worry about any private probation provider importing American CJS into the UK system, particularly when their contract is so close to its expiry date.

Are they doing so to make the service better? Or are they introducing initiatives and practices that they know will be outsourced and they hope to bid for when they are no longer probation providers?

'Getafix

If you are a prisoner who is located in an establishment in London or the Thames Valley and are due for release within the next few months, then you might be interested in an innovative prison-based resettlement programme called ‘Getting it Right’.

DeleteGetting it Right is a programme that MTC, the company which now runs London and Thames Valley Community Rehabilitation Companies, has brought across from the United States, where we run in a number of prisons. The programme recognises that many offenders need additional support to make a success of their move back into the community and Getting it Right is designed to do exactly what its name suggests and help get the whole process of resettlement right first time.

The programme is a flexible and offender-centred approach to resettlement. Typically delivered in the last 12 weeks of custody, ‘Getting it Right’ modules address a number of primary offender resettlement pathways, including: relapse prevention, social support and treatment needs, benefits advice and job hunting.

The programme is part of the Through the Gate offering, so the support is designed to continue as you make your journey back into the community. It includes the following modules, which can be customised to your own particular needs:

• Accommodation advice;

• Employment retention and brokerage;

• Financial advice;

• Signposting services for sex workers and victims of domestic and sexual abuse.

Research has identified a range of social factors that are linked to reoffending after release from prison. These include accommodation and ETE needs, and prisoners in the Surveying Prisoner Crime Reduction survey said that addressing these were two key factors in helping them to not reoffend. According to data from the Justice Data Lab, the interventions that are most proven to reduce reoffending are firstly employment, secondly education and thirdly accommodation.

Your Resettlement Coordinator will work with you to determine which modules you complete, based on your individual support needs. If you have been sentenced to less than four weeks in custody or are eligible for release on temporary licence or home detention curfew it is possible to deliver modules to you in the community.

As part of the programme, you will complete a Change Plan Journal which will give you an opportunity to explore your readiness to change and to develop a personal relapse prevention plan. You will complete the journal in your own time throughout the duration of the programme and these will be used in supervision sessions with your offender manager post-release.

Our experience from prisons in the US is that completion of the programme is likely to increase your chances of obtaining suitable accommodation and sustainable employment on your release.

Getting it Right is available to all of the more than 6,000 prisoners who reside in a London or Thames Valley resettlement prison and are managed by London or Thames Valley CRC, as well as those who are managed by the NPS, when they become due for release.

Getting it Right is a voluntary programme which you should be invited to take part in prior to your release, which means that you have to choose whether to take part. If you would like to take advantage of this but have not been invited, then don’t wait to be asked, but talk to your Resettlement Coordinator about it.