With domestic politics continuing to take some interesting turns - the Tories having privatised the electricity industry for ideological reasons, somewhat surprisingly I see they now want to try and stop the privateers ripping customers off lol - a comment left recently has served to remind me of the experience of former insider Julian Le Vay and his take on the politics behind the life and death of NOMS. Of course we may also see the demise of the MoJ as well....

NOMS: an obituaryThe National Offender Management Service, born 1 June 2004, died 8 February 2017. No flowers by request.

The abolition of NOMS last week greeted with a universal lack of interest. It will be little mourned, even though prisons and probation both did much better during NOMS' first decade than either before or since.

A difficult birth

NOMS was set up following a report by Pat Carter (1). Its conception was unnatural – a forced union of at least 3 different agendas: the introduction of 'end-to-end offender management', reducing the prison population and increasing competition. Its birth was troubled, with Blunkett announcing acceptance of its findings without adequate examination, or real understanding what they implied.

And it turned out to be malformed. Carter didn't go into detail and didn't test out his ideas. For example, he failed to notice that Government had no power either to run probation services directly or contract for them (which remained the case til Government legislated in 2007); or that about half of the resources for offender programmes were actually held outside the prison and probation services, so that making them 'commissioners' for such services missed half of the picture. His report also imagined a situation where the Department both ran prisons directly through line management and simultaneously 'commissioned' services from them, a legal and constitutional impossibility which, bizarrely, the current Lord Chancellor is about to re-attempt.

An unwelcome arrival

From the outset, NOMS was viscerally disliked by many in the prison and probation services, who knew full well how important is was to bridge the gap between custody and community services, but whose tribalism was too entrenched to be comfortable with a merged identity. Probation staff in particular understandably feared being dominated by the much bigger prison service, whose ethos it detested and whose demands for money and ministerial attention always trumped those of probation. All ministers believed in prison: some were dubious about probation.

NOMS was seen as a vehicle for ever increasing central control, exercised by a bloated and remote HQ. Figures banded about for the size and cost of NOMS HQ did not distinguish between classic civil service 'policy' jobs, and work that was fully operational and without which prison service couldn't have operated. It was an own goal that NOMS never produced any clearer account. (Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with centralisation. The chaotic, anarchic nature of the prison service up to the mid 1990s, where key operating instructions were causally ignored locally, sometimes because impossible to comply with, and terrible things shappened as a result, cried out for greater central grip. These things tend to go in cycles in large, distributed organisations.)

Endless surgery

If NOMS meant one big change, that would have been one thing – but the organisation was hacked about again and again.

Carter's notion of running prisons through both direct management and 'commissioning' – memorably described by Phil Wheatley as 'a plane that could never fly' – wasted years of constant reorganisation, trying to make this misconceived idea work, with the prison service separated out from NOMS as 'just another provider', before it was dropped in favour of plain ordinary line management. This constant shifting around – some units moved several times between the prison service, now deemed to be merely another provider, and the centre of NOMS – alienated many career civil servants in HQ.

Probation suffered from an especially bad case of what might be called 'Compulsive Re-organisation Syndrome' or CRS. First turned into the National Probation Service in the early 1990s, then into statutory Probation Trusts in the late 2000s, shortly before being broken up and part-privatised, part-centralised in the mid 2010s. Good people were exhausted, alienated or jettisoned along the way. What they must feel like now - as Government tells the prison service that empowering front line staff and freeing them from central control is - of course! - the way to improve services, and as the CRC contracts look more and more troubled. There is so much talk of accountability, yet no Minister is ever held to account for their botched or unnecessary re-organisations.

Missed opportunities

It can be said against NOMS that despite these massive re-organisations, it missed opportunities for getting real benefit from them. Prison and probation, far from being brought together, were cemented further into their silos. For example, there wasn't even an experiment in letting prison and probation services in an area as a single contract . Each prison and probation board or trust in an area continued to run their own offender programmes for the same bunch of offenders, instead of running a single programme across institutional borders.

And yet....it worked

And yet, for all that, the decade of NOMS invention was, looking back, a good one for both services – better than what went before , and certainly much better than what has come after.

...for prisons

The prisons system had been in a scandalous state for decades, right up to the turn of the century. But in the 2000s, with the introduction of effective management, a new generation of management minded governors, and substantial money for new offender programmes, there was steady improvement towards much more consistent performance (2). By 2010, the prison service was in a better state, despite continuing high over-crowding, than it had been in living memory.

Under the Prison Rating System, in 2010-11 no prison rated in the lowest category (cause for serious concern) and few in the next one up (cause of concern). Compare that with the turn of the century: a serious riot at Lincoln (2002), institutionalised beating in the Scrubs Seg, institutionalised racism at Brixton and many other prisons, the gruesome murder of Zahid Mubarek at Feltham, the near total collapse of Ashfield and Rye Hill! Or compare with 2015-16, when the PRS rated no fewer than 6 prisons as causing serious concern an a full quarter of the system rated as causing concern, and major riots at three prisons.

..for probation

Comparisons with probation's pre-NOMS performance is more difficult. Ironically, although prisons are often described as a 'hidden world', the media, and public, know what a 'bad ' prison looks like and excesses in prisons are (nowadays) pretty quickly made public. But 'failure', in probation, is not so easily recognised.

What one can is that far from being robbed of resources to pay the prison service, probation did very well in the 2000s.

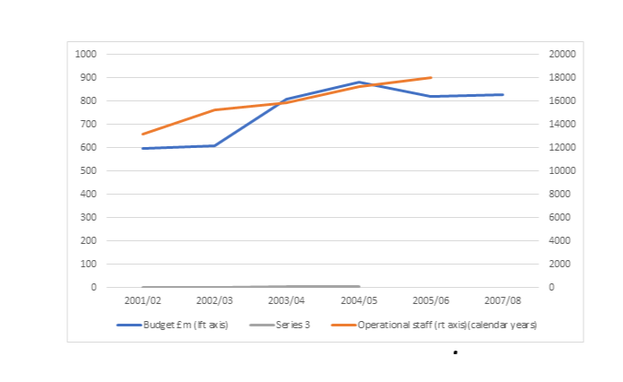

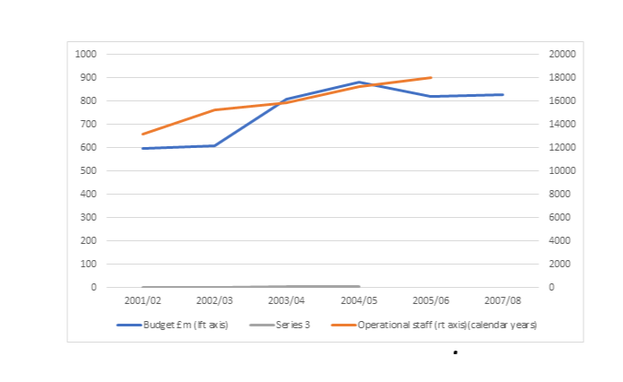

Graph 1: probation resources 2001-08

(from Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 2008 (3))

In fact, a study of resourcing of various criminal justice agencies in this period concludes that "probation appears to have been the main winner" (Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 2008), ahead of police, prisons and courts.

In the same decade there were many important advances in the way probation worked: the offender management model itself, which had faults to be sure, but some virtues, better methodologies for offender risk assessment, so crucial to probation (Oasys, VISOR), better inter agency working (MAPPA). And in terms of achievement one can point to the NOMS ratings report for 2010-2011, which found every single probation trust to be giving 'good' or 'exceptional' performance. One can also point to the extremely low rate of serious re-offending by the 50, 000 or so high risk offenders supervised under MAPPA every year; in 2010-11, 'only' 134 were charged with such an offence, and not all convicted, though of course it wil be said that that is 134 too many (4).

...success in cutting re-offending

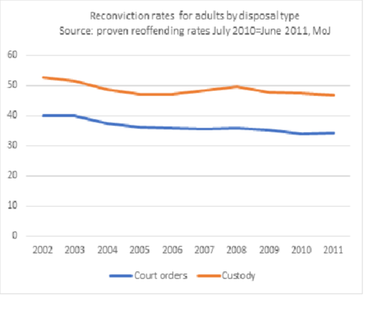

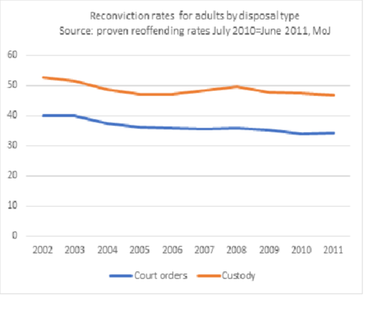

Many now say that the best, or indeed only, measure of the success of prisons and probation is the reconviction rate. I've expressed doubt about that in my last article here. But if that's what you think, have a look here, and then tell me why you still think NOMS in the 2000s was a disaster:

Graph 2: success in cutting re-offending 2001-2011

(Source: NOMS proven reoffending tables, 2010-11)

Granted it looks like a small reduction, but in fact it is as much as, if not more than, the criminological evidence suggests should be achievable, across the whole offender population. It amounts to many tens of thousands of crimes avoided. What's not to like?

(Indeed, it is very interesting to me that however often attention is drawn to this clear evidence of reduced reoffending, all you hear from politicians, pressure groups and criminologists is that reoffending rates have not come down. I am beginning to suspect that if there is one thing we really cannot handle, cannot accept, it is good news that conflicts with our deep belief that x or y is dreadful. We would much rather, it appears, that x or y continued to be dreadful, or at least seem so, than that we had to admit our prejudices are incorrect. One sees this in florid form in respect of many achievements of the Labour Government, where Labour supporters are far more insistent that nothing good was accomplished than the Tories are. It's a form of reputational self-harm. Because they weren't the right - or Left - sort of Labour Government, you see, so they just can't have achieved anything.)

The 2010s

I have talked of NOMS' success only in the 2000s. Of course, it was all downhill from around 2013. But one can hardly blame NOMS for that. Whatever the organisational structure, the cuts would have just as been severe, even more so because made without any attempt to manage them, and the mania for privatisation would still have struck. Indeed, NOMS became in a sense the victim of its own success: in a previous generation, the speed with which Grayling made succession of massive changes in prisons and probation would have been simply impossible. NOMS' greater managerial grip lent itself to Grayling's lust for successive massive, unargued, unevidenced, hasty re-organisations.

Verdict

NOMS was the ugly, unwanted child who was a quiet success. But none of us can bear to admit it.

Next up

So much for history. The question now of course is why Liz Truss has abolished it, why she has chosen to make the changes she has and what the chances are of them succeeding. I shall return to that question.

(from Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 2008 (3))

In fact, a study of resourcing of various criminal justice agencies in this period concludes that "probation appears to have been the main winner" (Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 2008), ahead of police, prisons and courts.

In the same decade there were many important advances in the way probation worked: the offender management model itself, which had faults to be sure, but some virtues, better methodologies for offender risk assessment, so crucial to probation (Oasys, VISOR), better inter agency working (MAPPA). And in terms of achievement one can point to the NOMS ratings report for 2010-2011, which found every single probation trust to be giving 'good' or 'exceptional' performance. One can also point to the extremely low rate of serious re-offending by the 50, 000 or so high risk offenders supervised under MAPPA every year; in 2010-11, 'only' 134 were charged with such an offence, and not all convicted, though of course it wil be said that that is 134 too many (4).

...success in cutting re-offending

Many now say that the best, or indeed only, measure of the success of prisons and probation is the reconviction rate. I've expressed doubt about that in my last article here. But if that's what you think, have a look here, and then tell me why you still think NOMS in the 2000s was a disaster:

Graph 2: success in cutting re-offending 2001-2011

(Source: NOMS proven reoffending tables, 2010-11)

Granted it looks like a small reduction, but in fact it is as much as, if not more than, the criminological evidence suggests should be achievable, across the whole offender population. It amounts to many tens of thousands of crimes avoided. What's not to like?

(Indeed, it is very interesting to me that however often attention is drawn to this clear evidence of reduced reoffending, all you hear from politicians, pressure groups and criminologists is that reoffending rates have not come down. I am beginning to suspect that if there is one thing we really cannot handle, cannot accept, it is good news that conflicts with our deep belief that x or y is dreadful. We would much rather, it appears, that x or y continued to be dreadful, or at least seem so, than that we had to admit our prejudices are incorrect. One sees this in florid form in respect of many achievements of the Labour Government, where Labour supporters are far more insistent that nothing good was accomplished than the Tories are. It's a form of reputational self-harm. Because they weren't the right - or Left - sort of Labour Government, you see, so they just can't have achieved anything.)

The 2010s

I have talked of NOMS' success only in the 2000s. Of course, it was all downhill from around 2013. But one can hardly blame NOMS for that. Whatever the organisational structure, the cuts would have just as been severe, even more so because made without any attempt to manage them, and the mania for privatisation would still have struck. Indeed, NOMS became in a sense the victim of its own success: in a previous generation, the speed with which Grayling made succession of massive changes in prisons and probation would have been simply impossible. NOMS' greater managerial grip lent itself to Grayling's lust for successive massive, unargued, unevidenced, hasty re-organisations.

Verdict

NOMS was the ugly, unwanted child who was a quiet success. But none of us can bear to admit it.

Next up

So much for history. The question now of course is why Liz Truss has abolished it, why she has chosen to make the changes she has and what the chances are of them succeeding. I shall return to that question.

Julian Le Vay

Notes

(1) 'Managing offenders, reducing crime ' (2003)

(2) It is de rigueur for criminologists decry 'the new public management' of the late 1990s: what species of management do they think existed in the early 1990s, when the prison service was a basket case? What kind of managerialism would be more acceptable to them?

(3) Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 'Criminal justice resources, staffing and workloads' (2008)

(4) MAPPA annual report 2010-11, statistical tables.

Notes

(1) 'Managing offenders, reducing crime ' (2003)

(2) It is de rigueur for criminologists decry 'the new public management' of the late 1990s: what species of management do they think existed in the early 1990s, when the prison service was a basket case? What kind of managerialism would be more acceptable to them?

(3) Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 'Criminal justice resources, staffing and workloads' (2008)

(4) MAPPA annual report 2010-11, statistical tables.

--oo00oo--

We've covered Julian's analysis of things before as here in 'Organising the Perfect Train Crash' and here 'A Future for Private Prisons?' and here 'A Possible Way Forward'.

We've covered Julian's analysis of things before as here in 'Organising the Perfect Train Crash' and here 'A Future for Private Prisons?' and here 'A Possible Way Forward'.

From Amazon:-

Competition for Prisons: Public or Private? Paperback – 16 Dec 2015

A quarter of century has passed since Margaret Thatcher launched one of her most controversial reforms, privately-run prisons, and the role of the private sector in delivering public services continues to be one of the big political issues of our time. This book, by a critical professional insider, re-assesses the benefits and failures of competition, how public and private prisons compare, the impact of competition on the public sector's performance, and how well Government has managed this peculiar 'quasi-market'. Drawing on first person interviews with key players, including Chief Executives and prison managers in both sectors and Chief Inspectors, Julian le Vay uses his former role as Finance Director of the Prison Service to give a wholly new analysis of comparative costs and of the impact of constant changes in competition policy. He draws out lessons from the parallel stories of the SERCO/G4S billing scandal, privately run immigration detention and the more radical approach now being taken on outsourcing probation, and looks in detail at four prisons, publicly and privately run, that 'failed'.Concluding with a critique of the future shape of competition, he also draws some general conclusions on the way government works. This is vital reading for anyone interested in the role of competition in public services, implementation of public policy, or the state of our prisons.

Julian Le Vay was Finance Director of HM Prison Service for five years, responsible for competitions to build and run prisons, then Director for Competition in the National Offender Management Service. Later he worked for two companies providing criminal justice services to Government. He is well placed to write about competition, having worked at different times on both sides of the fence.

Review

This is very convincing and clearly-written analysis of more than two decades of attempts to introduce competition across the criminal justice 'market' in the UK. It is both a salutary, and depressing tale. Real competition - repeatedly stymied by the extremes of either political inertia or over-action (none of which seems ever to be predictable) - is now under threat by a Ministry of Justice which does not appear to understand what real competition is, nor how to achieve it. The results of the enormously ambitious Transforming Rehabilitation programme remain to be seen, but on the basis of decades of previous experience the omens would not appear to be good. The tax-payer, professionals and service users - indeed the whole country - deserve a more intelligent approach to the management of a mixed-economy of service provision than the series of broken experiments repeatedly foisted on us in recent times. It remains to be seen what, if any, real progress will be made, but Le Vay's book is a clarion call for some new thinking in the area of criminal justice competition policy.

--oo00oo--

25 years ago, in the dying days of her government, Mrs Thatcher introduced the then quite improbable notion of contracting with the private sector to run prisons. This book reviews how competition has unfoldeded since then, including the public sector prison service's rather odd dual role, both as customer for and competitor with the private sector.

I contrast competition for prisons with examples of competition, or lack of it, in 'adjacent' services – immigration detention, electronic monitoring and probation – and contrast the story here with the very different one in Scotland. I conclude by answering the question whether competition has 'worked' - whether it has been worthwhile; whether it has been a legitimate enterprise, which some would contest; and whether it has a future.

Why did I write this book? First, It is an important story – one of the most controversial and also most complete examples of outsourcing public services, and one of the longest running. Second, I was fed up with people writing about it from prepared positions, sometimes from ideological preference, sometimes with vested interests. I wanted to tell the story just on the basis of the evidence. And last, the story formed the central part of my career.

To my surprise, the book ended up being as much about how well – or badly – we are governed as about prisons, or competition.

This is very convincing and clearly-written analysis of more than two decades of attempts to introduce competition across the criminal justice 'market' in the UK. It is both a salutary, and depressing tale. Real competition - repeatedly stymied by the extremes of either political inertia or over-action (none of which seems ever to be predictable) - is now under threat by a Ministry of Justice which does not appear to understand what real competition is, nor how to achieve it. The results of the enormously ambitious Transforming Rehabilitation programme remain to be seen, but on the basis of decades of previous experience the omens would not appear to be good. The tax-payer, professionals and service users - indeed the whole country - deserve a more intelligent approach to the management of a mixed-economy of service provision than the series of broken experiments repeatedly foisted on us in recent times. It remains to be seen what, if any, real progress will be made, but Le Vay's book is a clarion call for some new thinking in the area of criminal justice competition policy.

--oo00oo--

25 years ago, in the dying days of her government, Mrs Thatcher introduced the then quite improbable notion of contracting with the private sector to run prisons. This book reviews how competition has unfoldeded since then, including the public sector prison service's rather odd dual role, both as customer for and competitor with the private sector.

I contrast competition for prisons with examples of competition, or lack of it, in 'adjacent' services – immigration detention, electronic monitoring and probation – and contrast the story here with the very different one in Scotland. I conclude by answering the question whether competition has 'worked' - whether it has been worthwhile; whether it has been a legitimate enterprise, which some would contest; and whether it has a future.

Why did I write this book? First, It is an important story – one of the most controversial and also most complete examples of outsourcing public services, and one of the longest running. Second, I was fed up with people writing about it from prepared positions, sometimes from ideological preference, sometimes with vested interests. I wanted to tell the story just on the basis of the evidence. And last, the story formed the central part of my career.

To my surprise, the book ended up being as much about how well – or badly – we are governed as about prisons, or competition.

Julian Le Vay

This is worth a read alongside JLV's comments above:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.britsoccrim.org/volume2/005.pdf

That is a LONG read - I shall come back to it - it is WORTH archiving - Probation may have done well in the early 2000's in Le Vay's terms as far as resources was concerned and in some areas of performance but that was the era it was further removed from the oversight of local judiciary - (inner London was a special case) and there was the massive merger of the 5 Greater London Probation Service's led initially by a failed prison service governor.

ReplyDeleteHowever that was also the era where the rapid growth of staff without pre entry training changed the status of probation as a branch/partner to the social work profession.

But we need to look forward - Probation is clearly irrelevant to Theresa May because as Home secretary she dumped her plan - apparently agreed with the Secretary of State for Justice (Gove) to transfer probation to the PCCs & now more recently has chosen a general election over reforming probation as planned in April 2017.

I just hope it all holds together and the number of consequential lost lives and careers are minimal.

Re above comment "hope it all holds together" etc London CRC staff now starting to experience very tight micro target management indeed with frequent feedback demanded all the way up through the hierarchy. Success or failure seems to hang on our ability to click on various aspects of the cases on the system to a particular deadline. The reason given is that post inspection we must pull our socks up, that the MOJ scrutinise everything. There is a plan to direct us not to see any service users between 3 and 4 every day to allow time for the relevant ticks to be placed in the relevant boxes. At the same time admin support has been reduced to almost nothing and we are now responsible for personally undertaking almost every move on every case on our list. Simultaneously there are attempts to reduce costs, and this will affect the service users direct ( as will of course the meticulous obsessional box ticking which their officers are obliged to prioritise over and obove paying attention to their service users) :

ReplyDeleteThe paying of transport fares has been severely cut back and face to face interpreters are being strongly discouraged.

Oddly there is a plan to do away with group inductions in favour of one to one inductions. I am not sure if the rationale for this. It cannot be an attempt to improve practice with service users, who are clearly at the very bottom of the organisation's list of priorities. The change in induction practice will cost my team as a whole 10-12 hours per week. I wonder if this is designed to push certain of us over the edge in order to save redundancies or maybe to save the bother of disciplining people and elbowing us out that way. Elsewhere/ higher up there has been a cull of ACOs having to reapply for their own jobs, and now admin managers have been informed the same will soon apply to them.